When we visit a national park or look at the skyline of a city, often we do not enjoy a clear vista -- a white or brown haze hangs in the air and affects the view. This haze is not natural. It is caused by man-made air pollution, often carried by the wind hundreds of miles from where it originated.

Typical visual range in the eastern U.S. is 15 to 30 miles, or about one-third of what it would be without manmade air pollution. In the West, the typical visual range is 60 to 90 miles, or about one-half of the visual range under natural conditions. Haze diminishes the natural visual range.

Haze is caused by fine particles that scatter and absorb light before it reaches the observer. As the number of fine particles increases, more light is absorbed and scattered, resulting in less clarity, color, and visual range.

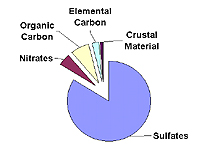

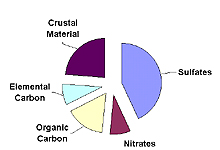

Contribution of Various Particulates to Haze

Eastern U.S.

Western U.S.

Five types of fine particles contribute to haze: sulfates, nitrates, organic carbon, elemental carbon, and crustal material. The importance of each type of particle varies across the U.S. and from season to season. The typical importance of each particle type in the eastern and western U.S. is shown in the figure to the right. Details on each particle type are provided below.

Sulfate particles form in the air from sulfur dioxide gas.

Most of this gas is released from coal-burning power plants

and other industrial sources, such as smelters, industrial

boilers, and oil refineries. Sulfates are the largest

contributor to haze in the eastern U.S., due to the region's

large number of coal-fired power plants. In humid environments,

sulfate particles grow rapidly to a size that is very

efficient at scattering light, thereby exacerbating the

problem in the east.

Organic carbon particles are emitted directly into the air

and also form there as a reaction of various gaseous hydrocarbons.

Sources of direct and indirect organic carbon particles

include vehicle exhaust, vehicle refueling, solvent evaporation

(e.g., paints), food cooking, and various commercial and

industrial sources. Gaseous hydrocarbons are also emitted

naturally from trees and from fires, but these sources

have only a small effect on overall visibility.

Nitrate particles form

in the air from nitrogen oxide gas. This gas is released

from virtually all combustion activities, especially those

involving cars, trucks, off-road engines (e.g., construction

equipment, lawn mowers, and boats), power plants, and

other industrial sources. Like sulfates, nitrates scatter

more light in humid environments.

Elemental carbon particles are very similar to soot. They are

smaller than most other particles and tend to absorb rather

than scatter light. The "brown clouds" often seen in winter

over urban areas and in mountain valleys can be largely

attributed to elemental carbon. These particles are emitted

directly into the air from virtually all combustion activities,

but are especially prevalent in diesel exhaust and smoke

from the burning of wood and waste.

Crustal material is very similar to dust. It enters the air

from dirt roads, fields, and other open spaces as a result

of wind, traffic, and other surface activities. Whereas

other types of particles form from the condensation and

growth of microscopic particles and gasses, crustal material

results from the crushing and grinding of larger, earth-born

material. Because it is difficult to reduce this material

to microscopic sizes, crustal material tends to be larger

than other particles and tends to fall from the air sooner,

contributing less to the overall effect of haze.

Haze generally appears either as uniform haze, layered haze, or plumes.

|

A uniform haze degrades visibility evenly across the

horizon and from the ground to a height well

above the highest features of the landscape.

Uniform haze often travels long distances

and covers large geographic areas, in which

case it is called a regional haze.

|

|

|

In a layered haze, you can see the top edge of the pollution

layer. This is often the case when pollution

is trapped near the ground beneath a temperature

inversion.

|

|

|

Plumes result from local sources. Plumes and plume-like

layers of elevated pollution take their shape

under certain meteorological condition where

the air is stable or constrained.

|

|

Some of the pollutants that

form haze have been linked to serious health effects and

environmental damage. Exposure to fine particles in the

air has been linked with increased respiratory illness,

decreased lung function, and premature death. For details, see the health effects page. In addition, sulfate and nitrate particles

contribute to acid rain, which can damage forests, reduce

fish populations, and erode buildings, historical monuments,

and even car paint.

To reduce haze we must reduce

emissions of haze-forming pollutants across broad areas

of the country. Cars, trucks, and industries are much

cleaner than they were in the past, and several programs

are in place to maintain this progress over the next several

years. Nonetheless, these programs by themselves are unlikely

to restore visibility to its natural conditions in many

protected areas.

In April 1999 the U.S. Environmental

Protection Agency (EPA) issued regulations to further

reduce haze and protect visibility across the country.

The EPA and federal land managers from other agencies

are working with state, local and tribal authorities to

promote steady improvements in visibility for decades

to come.

We are challenged to do

our part to help reduce air pollution. To learn more about

what you can do to reduce air pollution, see this EPA webpage.